****************

# 28

The

story of finding a card with a story

It

is April, 1998 and my wife and I are in Paris, at the famous Marché aux puces

de Saint-Ouen. An enormous market covering many streets and buildings that sells

antiques, collectibles and inexpensive clothing. Just try to find a secondary

used playing card here sometime. I follow my instincts. They have to be lying

around here somewhere. But, no, the only card I find is not lying around but

hanging up. It’s in a plastic file sheet on the wall behind a large desk on

which a surly Frenchwoman is working on a crossword puzzle. I stare from a

distance at a jack of spades.

|

|

From

here, it looks 18th century. In my best French, I ask if I

can see the card. “You’re looking at it right now,” says the lady

without looking up from her puzzle. My wife wants to leave the shop

right away, but I persist. This is the reason I’ve come to Paris. With

a sigh, the lady stands up and takes the plastic file sheet from the

wall. Before handing it to me, she tries to discourage me again. “The

other side isn’t as nice,” she warns me. My heart immediately skips

a beat. I turn the file sheet over. The back of the card has been

written upon. I summon all my acting talents and moan, “Ah” (Oh,

dear!), ”Mais non!” (It can’t be true!) and “Mon Dieu!” (My

God!). I then haggle the price at length because the card has been

written upon and has an ink spot. The lady takes the bait. “No,” I

say, “you don’t have to wrap it.” Outside, I tell my wife. It’s

a good thing the Frenchwoman doesn’t understand Dutch. |

Back

in our Paris hotel. My wife is already asleep but I want to take another look at

my acquisition. The only place where I can make light is the bathroom. There,

sitting on lid of the toilet, I admire the woodcut of the jack of spades colored

in with stencils. On the right, a little dog is jumping up onto his leg. Between

the jack’s legs, the maker has printed his name: Fournel Desvignes. Never

heard of him. I’ll have to look him up when we get home. The surface on the

right side of the card is damaged as if it had been stuck between a cupboard and

a wall. Or left on a stone floor with something heavy on top of it. I love

things that show traces of their ‘life’ - how they’ve ‘suffered and

survived’, dirty, damaged and worn. Therefore I do not clean or restore my

playing cards. I keep them as they are.

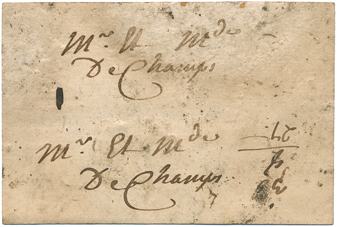

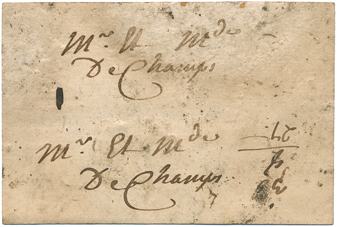

| The

back of this French card isn’t so pretty either. I didn’t exaggerate

this afternoon. Written twice in ink are the same names: Mr. and Mrs.

DeChamps. They were written quickly and smoothly like you would sign

your name. A sum is written as well: 38 with 8 underneath, a line and

then 27. Or is it 35? That would make more sense. Why would anyone write

a name twice on the back of a playing card? |

|

|

I

already have a couple of visiting cards made from playing cards in my

collection. Although never proven, everything points to the fact that

the visiting card originated sometime in the 18th century

when people started writing their names on the blank sides of playing

cards. |

|

The

traditional size of a conventional printed visiting card is practically

the same as that of a French playing card made during that time. To

economize on paperboard visiting cards have also been made on playing

cards cut in half. |

|

Everything

suddenly clicks into place: the card in which someone had written the names of

Mr. and Mrs. DeChamps twice was intended to be used as two visiting cards.

Either the ink spot or the sum of numbers had prevented this, but the card was

never cut and used.

Gejus

****************